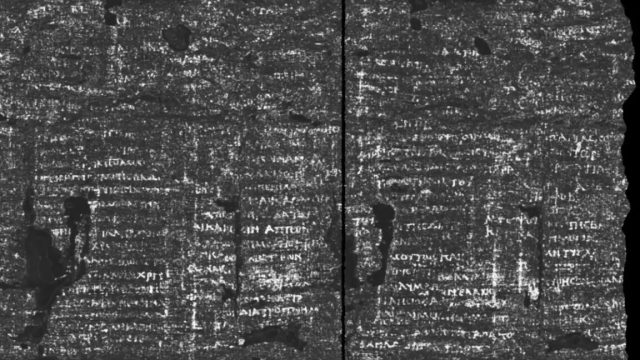

It is a regrettable actuality that there’s by no means time to cowl all of the attention-grabbing scientific tales we come throughout every month. Up to now, we have featured year-end roundups of cool science tales we (virtually) missed. This yr, we’re experimenting with a month-to-month assortment. February’s checklist consists of dancing sea turtles, the key to a wonderfully boiled egg, the most recent breakthrough in deciphering the Herculaneum scrolls, the invention of an Egyptian pharaoh’s tomb, and extra.

Dancing sea turtles

There’s rising proof that sure migratory animal species (turtles, birds, some species of fish) are capable of exploit the Earth’s magnetic area for navigation, utilizing it each as a compass to find out course and as a type of “map” to trace their geographical place whereas migrating. A paper printed within the journal Nature presents proof of a potential mechanism for this uncommon capability, at the very least in loggerhead sea turtles, who carry out an lively “dance” after they observe magnetic fields to a tasty snack.

Sea turtles make spectacular 8,000-mile migrations throughout oceans and have a tendency to return to the identical feeding and nesting websites. The authors consider they obtain this by their capability to recollect the magnetic signature of these areas and retailer them in a psychological map. To check that speculation, the scientists positioned juvenile sea turtles into two giant tanks of water outfitted with giant coils to create magnetic signatures at particular places throughout the tanks. One tank options such a location that had meals; the opposite had an analogous location with out meals.

They discovered that the ocean turtles within the first tank carried out distinctive “dancing” strikes after they arrived on the space related to meals: tilting their our bodies, dog-paddling, spinning in place, or elevating their head close to or above the floor of the water. Once they ran a second experiment utilizing completely different radio frequencies, they discovered that the change interfered with the turtles’ inner compass, and so they couldn’t orient themselves whereas swimming. The authors concluded that that is compelling proof that the ocean turtles can distinguish between magnetic fields, presumably counting on advanced chemical reactions, i.e., “magnetoreception.” The map sense, nonetheless, doubtless depends on a special mechanism.