Not lengthy after divorcing her fourth husband, Victor Andreasen, Danish author Tove Ditlevsen positioned a private advert within the newspaper of which he was then editor-in-chief. ‘Pursuits’, she wrote in Ekstra Bladet, ‘[include] literature, theatre, folks and home bliss.’ Lists are a recursive technique in Ditlevsen’s poetry, as are her fantasies of familial and home bliss. Love, she claims all through The Copenhagen Trilogy (1967-1971), is salvation, but in addition a drug. The skinny line between the 2 is extra totally realized in Present (Dependency, 1971), a confessional account of her marriages, amorous affairs and dependancy; the e book’s Danish title means each ‘married’ and ‘poison’. Nevertheless it’s in her poems that she most artfully transposes absence and presence, the void between having and wanting. Her poem ‘Marriage’ (1955) conjures a sobering analysis of conjugal life: ‘unknowingly coerced / right into a lawful demise of affection’.

There Lives a Younger Lady in Me Who Will Not Die (2025) – a brand new translation of Ditlevsen’s poetry that spans her total, 30-year writing profession – tells of a life by loneliness. Born right into a working-class household within the Vesterbro neighbourhood of Copenhagen in 1917, Ditlevsen had her first poem printed on the age of simply 20 in Wild Wheat. Inside three years, she had married one of many journal’s editors, Viggo F. Møller, who was 30 years her senior, and printed her first and much-lauded assortment, From a Lady’s Thoughts (1939), the works from which open There Lives a Younger Lady in Me Who Will Not Die. Though Ditlevsen initially attributed her early success to her first husband, she later claimed that it ‘most likely wasn’t essential to marry him to maneuver up on the earth, however nobody had ever informed me {that a} lady may make one thing of her personal’.

Higher recognized by English readers for her prose, Ditlevsen’s poetry has been usually dismissed as anachronistic. Discussing her work on the Danish TV present Retailer Danskere in 2005, as an example, the writer Klaus Rifbjerg known as her poems ‘effectively crafted and effectively formulated’ however ‘fairly quaint!’ Guided by the edicts of formal verse, her early work has a cadence that feels – even at her time of writing – decidedly twee. Take, as an example, ‘Eve’ (1942), during which the eponymous narrator cries to a star ‘so sadly – / no extra will these lips be kissed, these lips that kissed / gladly’. However for Ditlevsen, a poet dedicated to writing working-class literature, this was intentional. Refusing to yield to the elitist bent of excessive modernism, her work was well-liked precisely due to its sincerity. She was, above all else, a author prepared to put herself utterly naked.

A cynical impulse may surmise that the current revival of curiosity in Ditlevsen’s work from publishers is based on her business viability. Her work has continuously been in comparison with that of Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf on account of the truth that she tragically took her personal life on the age of 58 – a element this publication’s editors really feel crucial to say in her biography after a quick abstract of her staggering profession. In Harper’s, critic Lauren Oyler additionally took situation with Farrar, Straus and Giroux’s advertising of their 2021 reissue of The Copenhagen Trilogy, noting, ‘The work is vital; the destiny is merely a reality’.

Much less widespread, nevertheless, are the vital discussions of sophistication which are addressed within the foreword by fellow Danish poet Olga Ravn, who observes that Ditlevsen was not only a working-class author however a ‘employee’s author’ of proletarian literature to be taken critically. ‘The revolutionary topic, the employee,’ Ravn writes, ‘has at all times been presumed to be a person on the manufacturing unit. However when ladies carry youngsters into the world, youngsters who develop as much as go to the manufacturing unit, work is being finished.’

Insofar as her feminist politics knowledgeable her physique of labor, Ditlevsen wrote devastatingly in regards to the thankless, gendered injunctions of being a spouse and mom. She describes the unusual alienation of housekeeping and childrearing; she condemns the household, an establishment for which, she discerns in her poem ‘The Household’ (1969), ‘there isn’t any remedy’, its members figuring out her too effectively to like her and too little to look after her firm. Allusions to her experiences of home abuse and botched, unlawful abortions punctuate the poems with a visceral melancholy. On this approach, Ravn additionally attracts consideration to the truth that reception to Ditlevsen’s work continuously underplays, even erases, its radicality in favour of relegating it to the sketchy, imprecise class of ‘ladies’s writing’. To flatten Ditlevsen’s work in such phrases is to undermine not solely its place in feminist literature but in addition the singularity of her voice.

Tragedy could have performed its half in Ditlevsen’s life – however so did empathy. What provides mild and levity to There Lives a Younger Lady in Me Who Will Not Die is the writer’s solidarity with the topics about which she wrote. Her extraordinary social realism portrayed all walks of life: the poor and working-class, intercourse employees, widows, addicts, moms and youngsters. There are moments of consummate magnificence all through the gathering; a younger boy’s love for his grandmother; the narrator of ‘Childhood Road’ (1942) recalling the ‘rowdy and tough’ video games she used to play together with her brother. In compelling us to soak up these characters, Ditlevsen reminds us of the quiet, unremarkable lives that form the world. It’s actually a terrific disgrace that she died believing nobody cared for her poems. However, as she noticed in Barndom (Childhood, 1967), ‘I’ve to put in writing them as a result of it dulls the sorrow and longing in my coronary heart.’

Tove Ditlevsen’s There Lives a Younger Lady in Me Who Will Not Die (translated by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell) is printed by Penguin Classics within the UK

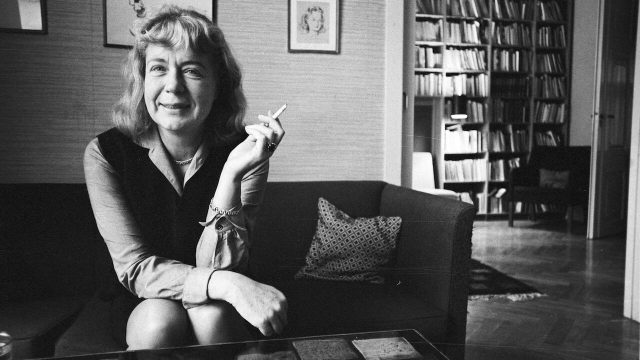

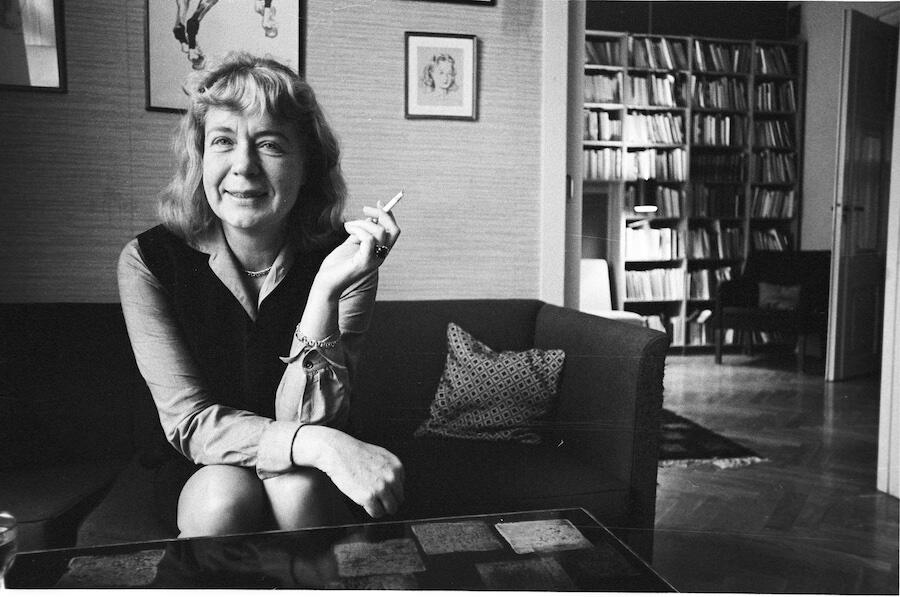

Most important picture: Portrait of Tove Ditlevsen. {Photograph} and courtesy: Alamo