One color roosts in one other within the title of Imani Perry’s new guide, Black in Blues: How a Colour Tells the Story of My Individuals (2025). Now, run the primary two phrases collectively: blacken blues. Black modulates blue, hatching a brand new hue; a number of refined variations ray out from this particular tint. Consider William H. Gass’s On Being Blue: A Philosophical Inquiry (1975), which opens with a gregarious listing of blue objects and entities. There’s additionally the painter protagonist of Percival Everett’s novel So A lot Blue (2017), who swirls collectively ‘phthalo blue, Prussian combined with indigo,’ and ‘cerulean mixing into cobalt’ to make a big summary portray.

But blue isn’t merely a color; it’s a vibration, a temper and a historical past that adheres to pores and skin, cloth and sound. Perry explores ‘the thriller… and… alchemy’ of blue within the lives of Black individuals; the essays transfer in an associative style, inching alongside by implication. She begins with a query posed to a cousin’s younger little one: ‘Which is your favorite coloration blue?’ They’re in Perry’s grandmother’s home, and the boy signifies a niche within the ceiling, by which ‘the unique blue of the room was seen… brilliant, just like the sky in August.’ We later study that through the Haitian Revolution, French troopers despatched aloft prayers of victory to the identical azure sky.

In different chapters, Perry follows indigo throughout continents, from Africa, the place the colourant was imbued with religious significance, to the plantations of the Americas, the place enslaved employees stained their palms within the service of a world market’s insatiable starvation for color. She lingers on the Center Passage – that huge ‘blue netherworld’ of dispossession. She reveals blue within the periwinkle beds of the American South, rigorously tended by enslaved individuals, and the delicate beads that among the enslaved managed to hold with them throughout the ocean. Examples abound of the ways in which the disenfranchised ‘normal themselves with care, whilst their lives had been thought-about fungible and never their very own.’ She additionally considers the blue uniforms of the Union Military through the American Civil Conflict – the color of liberation – and the coats of law enforcement officials, ‘metonym[s] for the enforcement arm of the state.’

Perry’s inquiry isn’t confined to materials tradition. Scouring slave narratives and different paperwork, she examines how within the Americas, ‘blue-black’ turned a fraught designation – a mark of simple African ancestry and, at occasions, a supply of each admiration and derision. ‘For some, it’s the grief of being near however not fairly white, or of carrying a strangeness inside Blackness that makes different Black individuals sceptical or resentful. For others, it’s the grief of being thought-about too Black even for Black individuals, [of] having a physique that’s marked as a sort of disgrace, as if blue-black flesh is a catastrophe,’ she writes.

Perry’s insights zig and zag, accumulate, overlap and even argue with each other.

However blue – essentially the most contrapuntal of colors – additionally possesses the facility to enchant. In Hoodoo custom, blue candles are burned for authorized victories, bluestones carried for luck in love and cobalt bottles hung from timber to beat back spirits. Perry traces this apotropaic thread, displaying how blue retained its cost, even in its most commodified types. One part considers the blue that sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois noticed in his late son’s eyes – a pale, betraying hue that exposed America’s tangled genealogies. Others mirror on the ‘slow-grind dancing’ referred to as the blues, the blue-black speller that taught abolitionist Frederick Douglass write, and the burden of blue within the artist Lorna Simpson’s 2019 present ‘Darkening’ at Hauser and Wirth, New York. Perry is very affecting when writing concerning the blues as a musical kind, describing its ‘tremor’ and its ‘nervous’ tone, the best way it bends with out breaking. It’s within the ‘animated swing’ of Miles Davis’s album Form of Blue (1959) and the sandpaper timber of Louis Armstrong intoning the titular query of his tune ‘(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue?’ (1951).

Standard historiography, in Perry’s phrases, usually asserts itself as ‘document-based imperial storytelling’. As a substitute, she works in a mode nearer to oral historical past and Hoodoo, ‘a data system born of disruption and cosmopolitanism.’ Her insights zig and zag, accumulate, overlap and even argue with each other. On this respect, she’s in league with the playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, who has envisioned her performs as a rebuke to ‘the Nice Gap of Historical past,’ which leaves swathes of African American historical past ‘unrecorded, dismembered, washed out.’ Parks goals, she wrote in The America Play and Different Works (1994), to seek out ‘the ancestral burial floor’ and ‘hear the bones sing.’

Perry seems to have set herself an identical problem: re-membering facets of Black historical past largely ignored or forgotten. A reader can quibble with the elisions entailed in an elliptical model. Perry’s dialogue of blue as a leitmotif in works of African literature feels glancing and suggestive somewhat than absolutely explored. Then once more, suggestion is the modus operandi of this good guide. The choice – conclusions that function as a sort of curfew on concepts – feels immeasurably worse. That’s not the case right here: the blue notes and bones sing on even after closing the guide.

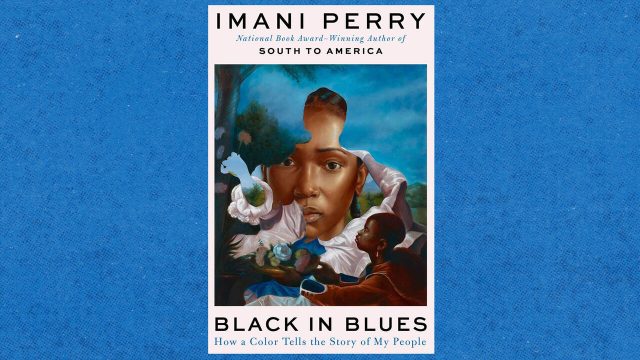

Imani Perry’s Black in Blues: How a Colour Tells the Story of My Individuals is out now from Ecco Press, New York

Titus Kaphar, Seeing By Time (element), 2018, oil on panel, 1.2 x 1.5 m, from the quilt of Imani Perry’s Black in Blues: How a Colour Tells the Story of My Individuals, 2025. Courtesy: the artist and Ecco Press