Final month, a sequence of wildfires devastated the Larger Los Angeles area, resulting in immense loss. Blocks and blocks of properties in Altadena and the Pacific Palisades are gone, generational properties and artist studios amongst them. At the least 29 folks died, with the loss of life toll anticipated to rise, in keeping with CBS Information.

The fires interrupted nearly each facet of LA’s artwork scene—together with the Getty Basis’s PST ART initiative, which opened final September and noticed greater than 60 exhibitions open throughout Southern California, supported by greater than $20 million in grants. Underneath the banner of “Artwork & Science Collide,” its exhibits targeted on local weather change, the setting, and Indigenous information. The final present to open as a part of PST is maybe the one most related to LA proper now.

That present is “Fireplace Kinship: Southern California Native Ecology and Artwork” at UCLA’s Fowler Museum, which has been within the works for round two years. It takes a sweeping take a look at fire-based land stewardship practices by 4 totally different Indigenous from Southern California (Tongva, Cahuilla, Luiseño, and Kumeyaay), the historical past of fireside suppression legal guidelines that outlawed this observe each through the Mission Interval and after California turned a state, and up to date efforts by the area’s Indigenous peoples to revitalize these fireplace stewardship practices. All of this with the purpose to rethink our relationship with fireplace, seeing it not as a harmful pressure, however as a substitute as kin, a being that may truly assist save the land.

In an announcement asserting the exhibition’s opening, Fowler director Silvia Forni wrote, “We perceive that in mild of the current wildfires and their aftermath, the phrase ‘fireplace’ could evoke worry, loss, and trauma. These feelings and this trauma are paramount and require our collective compassion and care as our communities heal. The Fireplace Kinship exhibition seeks to supply perception into and honor the knowledge of Indigenous fireplace stewardship and its potential to revive stability, cut back the danger of catastrophic fires, and renew the land for future generations.”

Marlene’ Dusek, Therapeutic your coronary heart and therapeutic sóoval with kúut (Marlene’ managing sumac gathering space, a vital plant relative for weaving), 2025.

Picture Kim Avalos

Along with the wealth of historic information on view, the exhibition additionally presents contributions by up to date Indigenous artists working in portray, sculpture, and video, in addition to conventional arts like basket weaving and canoe making. Whether or not by way of their supplies or their ideas, these artists present how cautious stewardship of their respective lands will be generative.

The exhibition’s opening was delayed two weeks by the wildfires, however it lastly was inaugurated on January 22. It’s curated by Daisy Ocampo Diaz (Caxcan), assistant professor of historical past on the California State College, San Bernardino; Lina Tejeda (Pomo), a graduate scholar analysis assistant at Cal State San Bernardino; and Michael Chavez (Tongva), a former Fowler archaeological collections supervisor and NAGPRA undertaking supervisor. As a part of their analysis and growth for the exhibition, the curators additionally fashioned an eight-person committee of group leaders all through from the 4 Southern California tribes.

To be taught extra about “Fireplace Kinship” (on view by way of July 13), ARTnews spoke to Ocampo Diaz by telephone in January shortly after the Fowler introduced that the exhibition’s opening could be postponed.

This interview has been edited and condensed for readability and concision.

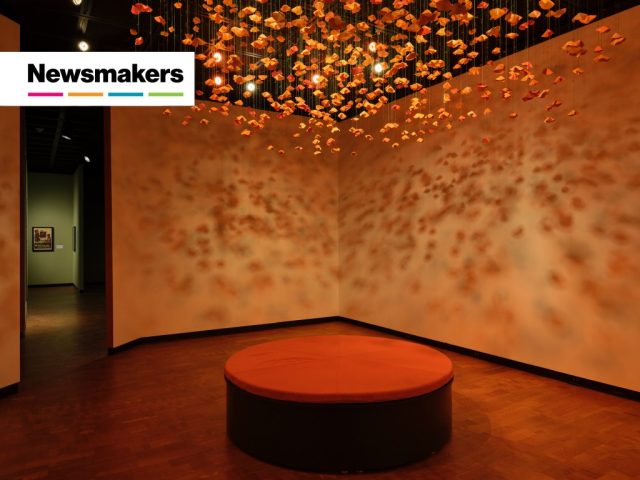

Set up view, “Fireplace Kinship: Southern California Native Ecology and Artwork,” 2025, at Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles, displaying works by Weshoyot Alvitre.

Picture Elon Schoenholz

ARTnews: How did the exhibition “Fireplace Kinship: Southern California Native Ecology and Artwork” come collectively?

Daisy Ocampo Diaz: My background is in public historical past, which incorporates museums and archives, in addition to Native American historical past. I’ve been working with tribes in Southern California for fairly a number of years. When the Fowler reached out to me [for this exhibition], I noticed this hole within the dialog about fireplace revitalization and together with Southern California in that discourse. I’ve saved up with the dialog of fireside revitalization in California Indian communities. What was clear to me was that there was a big concentrate on Northern and Central California, so one of many issues my co-curator, Lina Tejeda, and I wished to do with this exhibit was to cowl the geographic area of Southern California and the way this dialog of fireside revitalization applies right here.

Had you been eager about fireplace revitalization in your analysis previous to the present?

A part of my experience is in historic preservation, which is normally targeted on architectural preservation, however my space of focus is within the preservation of sacred websites. I analysis how cultural practices—and on this case, fireplace practices—are so crucial to sustaining landscapes, and that additionally consists of a whole lot of our sacred websites. My focus is basically talking land-based practices as a part of stewardship, with stewardship being a part of preservation. For instance, I’m a Caxcan girl, and our group relies in southern Zacatecas [in Mexico]. We burn our sacred mountain proper earlier than we’re able to clear sure land and slopes. That’s a part of our common observe. So, I’ve been working with the Chumash, water stewardship, and I’ve working with the Native American Land Conservancy, trying on the desert ecosystem and their work with the Previous Girl Mountains. I’ve been attempting to be of service to totally different tribal communities right here in Southern California.

Set up view, “Fireplace Kinship: Southern California Native Ecology and Artwork,” 2025, at Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles.

Picture Elon Schoenholz

The exhibition focuses on 4 totally different tribal communities inside southern California: Tongva, Cahuilla, Luiseño, and Kumeyaay. Why did you are feeling it was necessary to heart all these views versus only one?

I approached totally different tribal communities about their experience and their curiosity in collaborating. I wished to take a bigger geographic scope to Southern California as a substitute of specializing in one tribal group. The purpose additionally was for folk who will not be Native to know what tribal communities are in Southern California—and that’s going to be new for lots of parents. So, it was, in a means, an introduction of a subject, as a means of permitting every group to inform their very own story by way of their collection of objects, that are relations, beings, and a part of the group and are a part of this dialog of a fireplace.

Are you able to speak concerning the function of the eight-person committee of group leaders you assembled to advise on the exhibition and the perception they delivered to the undertaking?

The best way Lina and I approached fireplace was from a multivocal perspective from a number of communities. It’s not only one group informing this exhibit. There are totally different stakeholders. We had basket weavers, tribal fireplace departments, cultural practitioners, poets, and artists as stakeholders. Everyone seems to be telling that story of fireside. For instance, one concern is the prevention of the GSOB [gold-spotted oak borer], which is an invasive bug species that’s everywhere in the oak bushes. Everyone seems to be telling the story from totally different views, and each object and relative that’s a part of this exhibit comes with a narrative from that group and that individual, who additionally contributed to writing the wall labels. I included group at each stage of this course of.

Set up view, “Fireplace Kinship: Southern California Native Ecology and Artwork,” 2025, at Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles.

Courtesy Fowler Museum

How do you see works by the basket weavers as central to the exhibition’s narrative?

I constructed on the work of the California Indian Basketweavers’ Affiliation, a statewide group that has been dedicating fairly a little bit of their time to fireside revitalization. That’s as a result of the native ecosystem all through Southern California is 1) different and a couple of) getting stomped out by our cities and invasive species. There’s an actual want for basket weaving materials. The main focus of the present’s first room is trying on the construction of a basket to grasp which plant relations are a part of that creation of a basket—every part from Juncus to deergrass to yucca. These are all vegetation that really want fireplace to regenerate, in any other case they received’t seed. If there’s a Juncus patch that’s overgrown, it could possibly suffocate, so it actually wants fireplace to have the ability to proceed to have a wholesome array of basket materials. Basket weavers are specialists on the plant supplies that want fireplace. We use that dialog as an entrypoint to get to know not solely the ecosystem, but in addition the challenges of gathering plant materials at this time. That’s actually difficult, as is even getting a allow to burn in a small plot of land. We’re attempting to hit on all these totally different conversations.

How is the exhibition organized?

There are three sections, every with their very own room. The primary is “Our Fireplace Relative,” which is about redefining fireplace from a Southern California Indian perspective, not a fear-based understanding of wildfire. So it’s a type of re-centering. The second, “Fireplace Scars,” seems on the historical past of fireside suppression. Lina and I took an enormous archival deep dive, with the assistance of the Malki Museum, which facilitated entry to a whole lot of archival materials [and focuses on the preservation of Southern California Indian Cultures]. We checked out early settlers and explorers, if you wish to name them that. We checked out fireplace suppression through the Mission Interval, which truly features a important proclamation that outlawed managed fires [by Native people]. In California, we’ve traditionally dated fireplace suppression to the State of California in 1850–51, however in actuality, fireplace suppression is clearly documented within the Mission Interval. I wished to make that connection between fireplace suppression and settler colonialism—it generated the very overgrown, untended, and un-stewarded panorama that we see at this time that’s fueling all these wildfires. The final room, “Begging to Burn,” seems on the revitalization of fireside practices and the way totally different of us are collaborating in it. We usher in not simply elders but in addition youthful of us, of us who’re actively a part of their group.

Set up view, “Fireplace Kinship: Southern California Native Ecology and Artwork,” 2025, at Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles.

Picture Elon Schoenholz

Inside these three rooms, there are totally different up to date artists who’re grounding these totally different themes. There’s Weshoyot Alvitre, who’s Tongva; Leah Mata Fragua, who’s Chumash; and Emily Clarke, who’s Cahuilla. There’s additionally this thread of Native feminism all through the exhibit, in addition to the concept of panorama and creation. We’ve got a number of canoes by totally different maritime Native artists that had been commissioned for the present. One is Priscilla Ortiz, who’s Kumeyaay, and she or he labored with the Kumeyaay Group Faculty [in El Cajon]. They’ve been revitalizing their folks’s tule boats, and tule additionally want fireplace. We additionally labored with William “Willie” Pink, who’s Cupeño. He additionally created a canoe, which is a reproduction of a canoe that was present in Lake Elsinore, so it’s additionally a part of that revitalization.

In regard to fireside stewardship, are there variations in how every tribe approaches it?

There’s cultural burning, and there’s prescribed burning. Every has a unique goal. Cultural burning could be very particular sort and is both used to filter out some invasive species or for the oak bushes to smoke. The target isn’t just about fireplace; smoke can be very wholesome for lots of plant communities. Cultural burning on a Juncus patches is normally for weavers. Some of us are launched in fireplace revitalization from a extra institutional fireplace division perspective. Tribes usually have fireplace departments as a result of they should defend their reservation homeland. Additionally they should be ready for a wildfire. Studying how one can collaborate with totally different bureaucratic establishments can be tremendous necessary.

The fireplace stewardship that we’re pondering of as cultural burns are particular to every ecosystem. For instance, the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, who’re desert Cahuilla, speak concerning the desert fan palm, which is in Palm Springs and the Andreas Canyon. So in that case, we’re fireplace inside like a desert canyon ecosystem. I’d additionally say when every group is speaking about fireplace, they’re additionally speaking about their panorama, which could be very particular. A desert context is totally different from a San Diego, maritime, water-fire context.

Set up view, “Fireplace Kinship: Southern California Native Ecology and Artwork,” 2025, at Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles.

Picture Elon Schoenholz

The present’s description mentions desirous to reintroduce “fireplace as a generative component,” and the title “Fireplace Kinship” posits a familial relationship to fireside. Are you able to increase in your pondering for these to very poetic phrases? Why was this positionality necessary so that you can heart within the exhibition?

In a single dialog that Lina and I had with Myra Masiel-Zamora, a curator for the Pechanga Cultural Assets Middle, she talked about fireplace as a relative. This was additionally echoed by Marlene’ Dusek, who’s a fireplace practitioner. After we take into consideration fireplace as our relative, that adjustments how we work together with it. As a substitute of being one thing that we’re consistently attempting to flee as we’ve seen with wildfires, we are able to see it as a being that you just convey into your group to help in your relationship with the land. The main focus was that relationship, that relationality. The phrase that resonated essentially the most to everybody was kinship. Due to the wildfires, we could also be afraid to have interaction with fireplace, however nonetheless, there’s a relationship with fireplace. It’s wanted. It’s one thing that you just name into being to assist steward your land, steward your assets, and nourish you spiritually. Fires are additionally spiritually and culturally nourishing in a whole lot of contexts. There’s a small part in exhibition on cooking. I feel it’s additionally necessary not overlook our every day use of a fireplace and the way we’re in fixed dialog with it. That’s the place “kinship” got here into the title. We wished to consider relationships to fireside outdoors of a binary of all or nothing, good and unhealthy.

Set up view, “Fireplace Kinship: Southern California Native Ecology and Artwork,” 2025, at Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles.

Picture Elon Schoenholz

The current wildfires have been so devastating—they even delayed the exhibition’s opening. However sadly, they aren’t a brand new phenomenon in South California. In a means, this present was all the time going to be related to this group, however it’s positively taken on new resonance now. What do you hope folks take away from the present?

I used to be born and raised in LA. I moved out right here to Riverside in my early 20s to attend UC Riverside. I’m consistently on the 60 Freeway, nonetheless forwards and backwards, with my household. Whereas we’ve been curating this exhibition, there have been a number of fires, not simply the Palisades and Eaton fires. We’ve had catastrophic fires all all through the Inland Empire, just like the Line Fireplace in San Bernardino [in September 2024]. I say that to not concentrate on who’s had it worse, however to clarify the understanding that we’re all a part of a panorama. One factor that will get misplaced, residing in such an enormous metropolis like LA, is that you just’re a part of the land. You develop into a part of a ZIP code, a neighborhood, a bus route. You get right into a routine round all these totally different factors, however these are by no means truly geographic and panorama factors in ways in which residing in a smaller city with proximity to mountains and rivers would offer.

I hope that folk within the metropolis can actually take into consideration themselves as folks of a spot and take into consideration our vulnerability and our relationship with fireplace. That’s going to be difficult. I don’t take that calmly as a result of this transfer to revitalization of fireside stewardship inside Native communities is considerably of a contradiction. How are you going to ask somebody to have a relationship with fireplace when it simply burned down their home? There’s a whole lot of unlearning concerned, and I hope the exhibition will be the start of that dialog for folk. There’s what our intention with this exhibition is: beginning a brand new dialog about how all of us should be fire-adaptive. Southern California Indian folks have all the time been fireplace adaptive. They had been all the time partaking fireplace. However that’s not essentially a part of an LA identification. The truth is that we do now should be fire-adapted communities, each Native and non-native of us.

Correction, Monday, 17, 2025: An earlier model of this text misstated the institutional affiliations of cocurators Daisy Ocampo Diaz and Lina Tejeda. They’re at California State College, San Bernardino.