Panjereh is the Farsi phrase for ‘window’, ‘portal’ or ‘passageway’. It’s additionally the title of Sheida Soleimani’s first New York institutional solo present, at the moment on view on the Worldwide Heart of Pictures. The exhibition, which is able to journey to the Modern Arts Heart Cincinnati in October, homes a number of the Iranian-American artist’s most private and bold work thus far, together with her notable ‘Ghostwriter’ (2021–ongoing) sequence.

‘I’ve wished to make pictures about my household’s story, and about my mother and father, since my undergraduate days,’ Soleimani tells me. ‘With “Ghostwriter”, I really feel like I lastly discovered the language, the power and the boldness wanted to do that correctly.’

The 35-year-old has made a reputation for herself together with her signature model, which updates the Dadaist photomontage for our digital age. In her house studio in Windfall, she pictures dense tableaux that burst with a dizzying surfeit of reference and that means, combining fragments of pictures sourced on-line with crude handcrafted photo-sculptures, discovered objects, valuable heirlooms and, typically, folks. Utilizing a medium-format digital camera and a small aperture setting to make sure that the totally different elements all seem in equally sharp focus, Soleimani compresses the space-time of this energetic constellation right into a two-dimensional picture that’s concurrently seductive and grotesque. Over the previous decade, she has used this technique to deal with totally different, however all the time political, topic issues – from a memorialization of victims of the Iranian regime’s human rights abuses (‘To Oblivion’, 2016–17) to a campy send-up of the worldwide oil trade’s energy gamers (‘Medium of Trade’, 2017–18).

‘Ghostwriter’ marks an evolution for the artist. The sequence focuses on household historical past – particularly, her mother and father’ political exile from Iran. Her father and mom, a health care provider and nurse respectively, had been pro-democracy activists crucial of each the Shah and the Ayatollah, and so they confronted persecution following the 1979 revolution. He spent three years in hiding earlier than fleeing the nation in 1984. She was imprisoned and put in solitary confinement earlier than she may go away and be a part of her husband two years later. They ultimately settled close to Cincinnati, the place Soleimani grew up. Because the undertaking’s title suggests, Soleimani adapts her distinctive visible language as an instance key episodes from her mother and father’ lives on their behalf.

The sequence is a form of survivor testimony.

‘It was vital that this work was collaborative,’ she explains, ‘that it didn’t fetishize their trauma however, as an alternative, recorded their harrowing tales so they’d have a everlasting place in historical past. The sequence is a form of survivor testimony.’ The ‘ghost’ within the title refers to each the creator and her topics; her spellbinding photographs reverse the traumatic limbo of her mother and father’ exile by remembering their pasts as each fantasy and historical past.

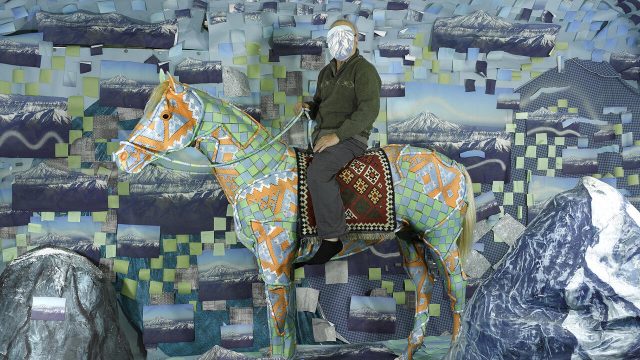

Soleimani describes her strategy as ‘magical realism’. Akin to the literary style, distinctions between determine and floor, picture and object, time and place, fantasy and actuality, historical past and fantasy, archive and reminiscence, are all scrambled in photographs redolent with symbolism. Acquainted photographic genres – the studio portrait, the ethnographic diorama, the nonetheless life – are infused with have an effect on, humour and play. Deliverance (2024), Soleimani’s illustration of her father’s treacherous escape on horseback over the Zagros Mountains into Turkey, is a tongue-in-cheek nod to the custom of heroic equestrian portraits. In it he seems astride a fibreglass horse upholstered in a chequerboard material screen-printed by hand, the sample being a core motif on this sequence.

‘When my mother and father every fled – at totally different instances – they had been, in essence, pressured to play a sport: a sport of luck and likelihood. My fascination with gameboards – checkers, Snakes and Ladders – emerges from this,’ Soleimani notes. ‘What are the video games of danger that refugees and immigrants should play to outlive? Can they climb the ladder, or will the snake deliver them crashing again down?’

Soleimani typically makes use of this sample, which additionally remembers Photoshop’s transparency grid, to loosely construction her photo-montaged backdrops; at different instances, she approximates it by affixing squares of colored paper to the surfaces of these backdrops. The pixelation of the low-resolution pictures she usually makes use of to assemble these backgrounds seems to unfold virally, additional compromising their legibility. ‘The fractured gameboard turns into the visible and conceptual backdrop to those narratives, laying the muse for the way layered, unsure and deeply difficult these tales really are,’ she explains.

If Deliverance marks departure, Behest Zahra (2023) imagines an unlikely return. The work reveals her father seated cross-legged, cupping filth in his arms, on a pink Persian carpet inside a makeshift – however efficient – re-creation of the part of the titular cemetery (Behesht-e Zahra). Many murdered dissidents are buried there, their graves desecrated by the regime with a purpose to erase these activists from historical past. One of many first issues Soleimani’s mother and father bought as a married couple, the carpet is a treasured memento her father carried with him into exile.

Soleimani’s frames and apertures assert images’s potential as a device of crucial fabulation – a portal by way of which to bridge previous and current.

Although her mother and father seem in most of the pictures on view, we by no means see their faces. They both put on crude paper masks or flip away from the digital camera. Whereas preserving their anonymity and deflecting the digital camera’s inquisitive and objectifying gaze, this technique additionally focuses our consideration on their physique language and gestures. Soleimani emphasizes this in a sequence of smaller compositions that zoom in on her mother and father’ arms or arms. Throughout ‘Ghostwriter’, the gesturing hand turns into an index of care, a hint of lingering trauma, an expression of longing and a provider of reminiscence. In Behest Zahra, her father’s cupped arms embody his grief – each for his martyred comrades and for a misplaced homeland.

Birds, lifeless and alive, additionally seem steadily on this sequence: a spillover – lengthy resisted – from Soleimani’s parallel follow as a federally licensed wildlife rehabilitator. ‘I wished to guard my sufferers,’ she says of the avians. ‘I didn’t need them to endure the projection that so usually accompanies images or be topic to the perceptions people have of them, to the symbols and roles they assign to them. Take into account all of the concepts – purity, hope, peace, misfortune, demise – now we have hooked up to those creatures for hundreds of years in artwork, literature and movie, all primarily based on how they give the impression of being, the sounds they make. I would like these creatures to be free from these confines and to create their very own narratives.’

Many of the birds that Soleimani cares for at her clinic Congress of the Birds are harmed by human infrastructure throughout their annual migrations. The stay ones that seem in ‘Ghostwriter’ have usually simply recovered from such accidents and there may be each an intimacy and an idiosyncrasy in how Soleimani chooses to painting them. In Midday-o-namak (2021) and Khooroos named Manoocher (2021), her mother and father – posed formally, seated in three-quarter profile – unexpectedly, tenderly, every cradle a special fowl of their arms.

‘My relationship with my mom – who was unable to proceed her occupation in exile and redirected her caregiving instincts in direction of birds and animals – has all the time concerned the caretaking of untamed animals, making an attempt to heal them and returning them again to the wild,’ the artist recounts. ‘Once I started conceiving this sequence, I began serious about lineages of care, about caretaking as inheritance.’ Somewhat than clichéd associations with flight and freedom, the birds embody the actual dangers, bodily and psychological, that migrants, be they human or more-than-human, face and overcome. They seem not as metaphor however, maybe, a sort of kin; their presence, like that of her mother and father, testifies to their survival.

To those referentially wealthy photographs, Soleimani provides a extra restrained register, nesting excessive close-ups of injured birds in her care in pictures her mom shot in Iran earlier than she left (on movie that was solely not too long ago developed). Taken with a close-up package, these photographs power an excessive proximity to their distressed topics that may make them exhausting to see, each visually and viscerally. Within the subdued palette and inchoate types of her mom’s pictures, any promise of an archival retrieval of the previous softens into subjective impressions of color, mild and texture, acknowledging the inevitable fallibility of reminiscence. Particulars from sketches made by her mom are overlaid: squares and rectangles, home windows and doorways, some barred and a few barely ajar. Soleimani’s frames and apertures are metaphors, too, asserting images’s potential as a device of crucial fabulation – a portal by way of which to bridge previous and current, story and historical past.

Sheida Soleimani’s ‘Panjereh’ is on view at Worldwide Heart of Pictures, New York till 28 September, and can open at Modern Arts Heart Cincinnati on 24 October

Foremost picture: Sheida Soleimani, Deliverance (element), 2024, pigment print, 229 × 183 cm (unframed). Courtesy: © Sheida Soleimani, Courtesy Edel Assanti, London and Harlan Levey Initiatives, Brussels